Hergé’s comic-book hero is about to enthral a new generation in a Spielberg film. But who was he modelled on? Tony Paterson reports

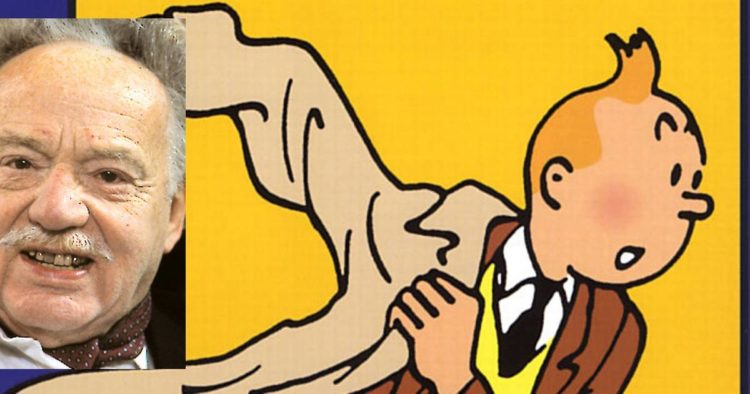

Palle Huld, left, travelled the world in 44 days by ship, train and car after winning a competition in a newspaper. His book about his journey was said to have inspired Hergé to create Tintin, right.

Palle Huld, left, travelled the world in 44 days by ship, train and car after winning a competition in a newspaper. His book about his journey was said to have inspired Hergé to create Tintin, right.Pictured standing gingerly in a doorway at the office of the Danish newspaper Politiken over 80 years ago, Palle Huld looks more like a timid and very junior character in a Bertie Wooster novel than the adventurous youth who is said to have inspired Hergé’s legendary comic-book character Tintin.

Yet a closer look at the black and white photograph taken in 1928 provides a clue to excite students of the tufty-haired boy reporter. Fifteen-year old Huld, it emerges, is wearing the neatly pressed plus fours that have been Tintin’s sartorial hallmark for decades. Had colour photography been invented at the time, it would also have been apparent that like Hergé’s character, Huld has red hair.

Albums about Tintin’s adventures have sold more than 200 million copies world wide since they first started appearing as comic strips 81 years ago. As testimony to his enduring popularity, a feature film produced by Steven Spielberg entitled The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn will hit cinema screens world wide before Christmas.

Tintin remains a global best-seller. Yet the identity of the person who inspired the great comic-book author’s central character has remained elusive.

Tintinologists have spent the past 27 years since George Remi’s (alias Hergé’s) death in 1983 trying to find a definitive answer. There are scores of theories. Huld certainly helped to generate the character of Tintin. He may even have been his true inspiration.

Danish newspapers reported Huld’s death at the weekend aged 98. He spent most of his life as an actor, but his real claim to fame as the man who inspired Tintin occurred years earlier in 1928. Having left school at 15, Huld was doing a humdrum job as a junior clerk in a Copenhagen car company when one day he decided to answer a newspaper advertisement.

The Danish daily Politiken was holding a contest to honour the centennial of Jules Verne. Its aim was to re-enact Phileas Fogg’s famous voyage of Around The World in Eighty Days, described in Verne’s celebrated 1873 novel. Yet this time around the contest was open only to teenage boys and the winner, who had to circle the globe unaccompanied, had to complete the journey in 46 days using every form of travel barring aeroplanes.

Huld, who had shown his adventurous spirit as a Boy Scout, was selected from several hundred teenagers who had applied to Politiken. He left Denmark on 1 March 1928 and circled the globe, travelling by steam train and steamship through England, Scotland, Canada, Japan, the Soviet Union, Poland and Germany. “Something in me had to try it,” Huld wrote in his 1992 autobiography.

The world’s press covered Huld’s voyage throughout. His train pulled out of Copenhagen station at the start of his trip and all the way across Denmark crowds stood by the track and at railway stations waving flags and offering small gifts for the voyage.

The journey passed off without incident until Huld reached Canada. Wanting to impress a young girl he had met on the boat crossing the Atlantic, he took an unscheduled tour of St John’s and missed his train connection. To make up lost time, he had to board a special trains used by emigrants.

The journey passed off without incident until Huld reached Canada. Wanting to impress a young girl he had met on the boat crossing the Atlantic, he took an unscheduled tour of St John’s and missed his train connection. To make up lost time, he had to board a special trains used by emigrants.

After crossing to Japan, Huld faced the challenge of crossing the then war-torn region of Manchuria in what is now north-east China. In 1928 Manchuria was at the centre of a dispute between the Soviet Union and Japan, which was trying to gain a foothold in the region. Huld managed to get through Manchuria without problems.

He was given his biggest fright in Moscow where he arrived to find that no one was there to meet him. At a time when foreigners in Moscow were arrested simply for going out without an escort, he toured the city in a horse-drawn cab for hours searching for the Danish consulate. He finally stopped off at the Hotel Europa where he asked staff to telephone the consulate and send someone to meet him.

When Huld finally returned to Copenhagen after 44 days, there were 20,000 people there to welcome him home. His journey ended on the shoulders of two burly policemen who waded through the crowds and carried him to his waiting family. His mother had been prescribed sleeping pills for the whole of his trip.

The young Huld wrote an account of his adventures which was published in several languages including English, in which it appeared in 1929 as A Boy Scout Around The World. It is known that Hergé read Huld’s account. It was perhaps no coincidence that the character of Tintin surfaced for the first time the same year in Le Petit Vingtieme, the children’s section of a Belgian newspaper. Palle Huld was happy to encourage the notion that he was Hergé’s inspiration for Tintin. But Hergé, who delighted in utterly baffling Tintinologists by using the phrase “Tintin c’est moi,” liked to keep the source of his world-renowned character shrouded in mystery.

The issue has kept Tintinologists guessing ever since Hergé’s death. More than a decade ago, Huld’s claims to be Tintin’s inspiration were at least partially undermined by the writer and researcher Jean-Paul Schulz who concluded that Tintin was based on the real life French journalist Robert Sexe.

Sexe was a Great War correspondent and like Tintin, a motorcycle fan, who never stopped exploring. He not only looked and dressed like Tintin, but his best friend was called Milhoux, which is the phonetic translation of Tintin’s faithful dog, Milou – called Snowy in English.

Moscow was Sexe’s first foreign reporting destination in 1926. Three years later Hergé published his first Tintin book, Tintin Au Pays des Soviets. The chronology of Sexe’s subsequent foreign trips to the Congo in 1930 and America in 1931 corresponds exactly with the chronology of the first three Tintin volumes.

Even the Hergé foundation in Brussels has admitted that the similarities are striking and that some of the drawings in the Hergé books appear to have been inspired by photographs taken by Sexe during his travels. There is no evidence that Hergé ever met Sexe. However Tintinologists have concluded that Hergé almost certainly closely followed the accounts of Sexe’s adventures because they were published extensively in Belgian newspapers.

Yet there are many other possible sources of inspiration for Tintin. They include Hergé’s younger brother, Paul Remi, a career soldier who shaved his hair and grew Tintin-style “hair spikes”, and a fellow student of Hergé’s called Charles who wore plus fours and Argyle socks. The choice is enough to keep Tintinologists active for decades to come.

It is both possible and plausible that all these influences, including the globe-girdling adventures of Palle Huld, helped in the making of the famous boy reporter with a red quiff, plus fours and a faithful companion called Snowy. Hergé used to refer to his character as his “personal expression.” He once complained: “If he is to go on living, it will be by a sort of artificial respiration.” Steven Spielberg would no doubt conclude that Hergé was wrong on that one.

Leave a Reply